- Who We Are

- How We Work

- Regional / Country Initiatives

- Legacy

- Core Themes

- Working Groups

- Portfolio & Results

- Newsroom

- Resources

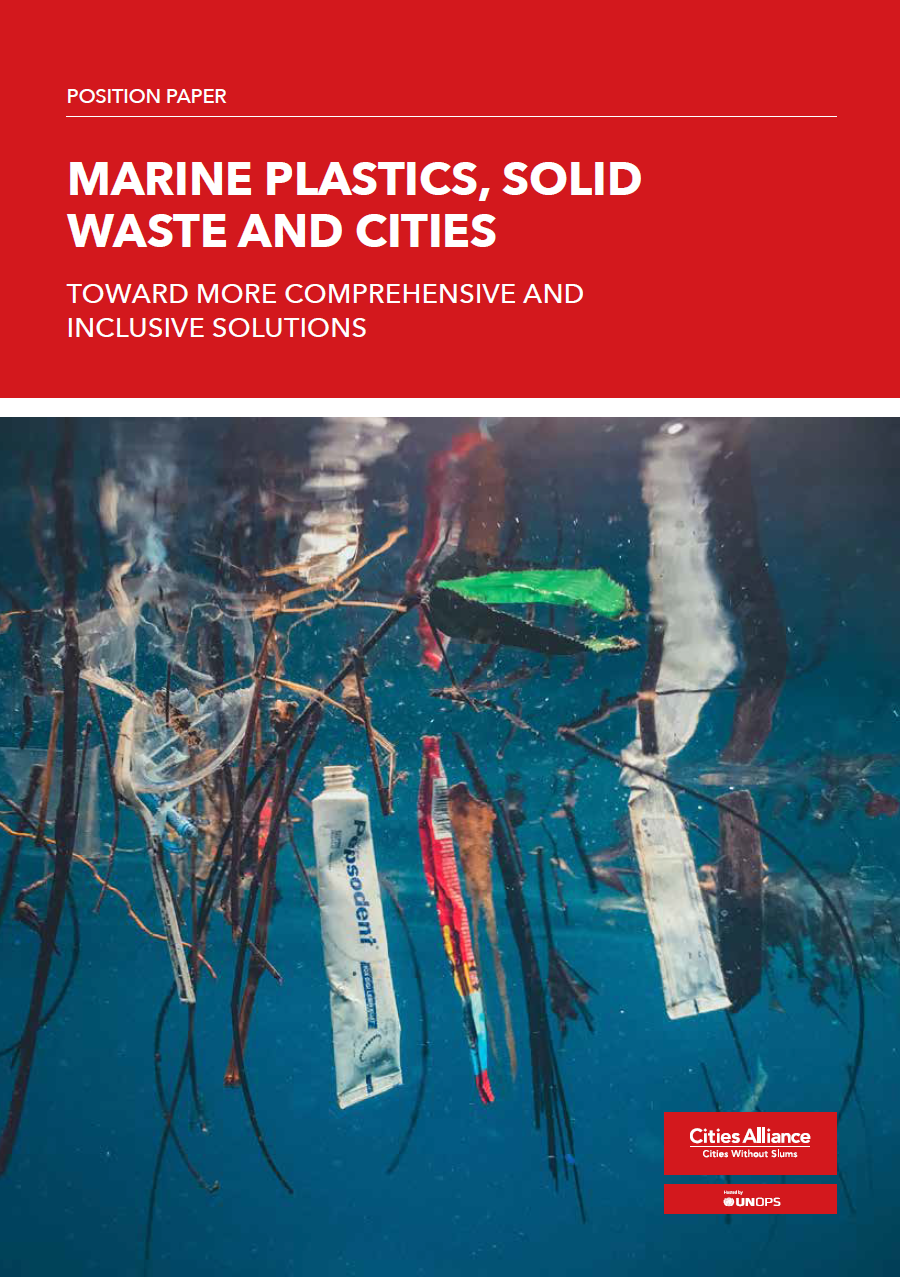

Marine Plastics, Solid Waste and Cities

This paper explores the role that municipal governments and informal waste pickers can play in the fight against Marine Plastic Pollution (MPP).

One of the great environmental threats of our time, MPP causes an array of negative environmental impacts that will worsen in the coming years if current trends persist. Cities are key centres of production for both MPP and social inequality, and therefore central to the causes of this crisis and potential solutions.

This dual production of MPP and social inequality suggests a two-pronged approach to solving both problems is needed – one that focuses on inclusive solutions downstream and policy and societal changes upstream. Such an approach can incentivise the social value of economic resources and minimise the long‑term negative externalities of diverse modes of production and consumption.

Solving the MPP crisis begins with broadening the scope of analysis of the waste and plastics value chain and its impacts to include the informal sector.

This paper focuses on Global South countries, where solid waste management systems tend to be underfunded and inadequate. They are also where global waste is likely to increase the most. This is not to excuse the Global North from its responsibility in the MPP crisis; these countries developed many of the technologies, materials, and systems involved, and they are among the main drivers of global consumption. In addition, many Global North industries are based in or process goods in the Global South, where they directly impact the environment.

In the cities of the Global South, waste can represent opportunity. A veritable army of informal environmental agents is already actively contributing to reducing plastic waste and pollution. These informal waste pickers represent both a vulnerable and productive group.

Key messages:

Social inequality is built into the waste and recycling value chain at every stage and level, but cities are where these intrinsic inequalities are most manifest. Yet, these social dynamics of the broader materials value chain are not always considered in the assessment and design of MSWM systems, which tend to focus on purely technical aspects. A comprehensive approach to the MPP crisis and its solutions should consider the urban poor as both an affected group and – when properly engaged, supported and integrated – a potential part of the solution.

Solving the MPP crisis requires a comprehensive approach covering both the downstream and upstream phases. While the effectiveness of MSWM systems plays a major role in determining how plastic waste will enter the environment, the upstream phases of production and consumption determine the production and dissemination of the materials that will later become plastic waste.

Local governments are essential to the global effort to end MPP and create more inclusive systems. Increasing or facilitating their access to funding, specialised knowledge, and appropriate technologies, as well as their inclusion in global and national discussions around SWM issues, can help local governments adopt more comprehensive and cohesive actions to prevent, address, and reduce plastic waste.

The complexity of urban systems demands integrated and collaborative arrangements. Inadequate practices and behaviours by producers, consumers, and SWM authorities lie at the root of the MPP problem. Changing these will require all system actors – national and local governments, businesses, consumers, and the general public – to change existing attitudes and practices around solid waste in general and plastics in particular.

Technologies should be appropriate to the existing context. Recognising and integrating local cultural and social norms, skills, capacities, and knowledge – as well as resource constraints on construction, maintenance and repair – can help increase the uptake and sustainability of new SWM practices. The challenges of expanding and upgrading MSWM systems to meet growing demand has led many cities to experiment with community-based schemes and technologies, as opposed to capital-intensive formal sector solutions.